When my parents came to the United States, they would send money back home to our family back in Taiwan. When my grandparents fled to Taiwan, they would send money back to China. It’s a common immigrant tale and one repeated over and over again.

When someone is able to get to the land of opportunity, you want to share that wealth with your family back home where the opportunities are fewer and farther apart.

When I got my first paycheck, I sent my parents 10% of that first direct deposit.

It was a symbolic gesture but an important one. Traditions are important.

And it was also a small amount, so there was never any concern that it could trigger the gift tax. For most gifts, the gift tax is hardly a concern.

But when it’s part of an estate planning move, the gift tax can be a very big deal.

Maybe you’ve heard of the gift tax, and perhaps even bumped up against it. For most people, the gift tax is something of a gray area in the tax code. They may know it exists, but how and when it applies is another story.

Let’s demystify it right now.

Table of Contents

🔃Updated February 2024 Updated to reflect the updated estate tax exclusion figure (increased to $13,610,000) as well as gift tax exemption limits (increased to $18,000 a year).

The Basics of the Gift Tax

The gift tax and the estate tax are closely related, and often even mentioned in the same sentence or discussion. There are practical reasons for that.

The estate tax was put into place to collect tax on assets transferred from the wealthy to their children and other beneficiaries. It was largely seen as an equalizer, moving a substantial chunk of the wealth of very prosperous families to purposes related to the general public.

Like many other tax types, the estate tax allows for certain exemptions. For example, for 2024, an estate worth up to $13,610,000 can be transferred from an individual to his or her heirs without incurring the tax. A married couple can transfer up to twice that – $27.22 million.

That’s a ton of money. (when you hear someone complain about the estate tax, they’re either complaining aspirationally or you just learned how much money they have!)

The estate tax was designed with the extremely wealthy in mind. An estate exceeding $13.61 million is not extremely rare given the collective value of real estate, retirement plans, stock portfolios, business interests, and insurance policy proceeds (the latter aren’t generally taxable but are added to an estate for estate tax purposes). It’s not common but also not extremely rare.

If you have a lot of money, one way to avoid the estate tax is to give it all away before you die. That’s where the gift tax comes in.

The gift tax applies when an individual starts transferring money to people before they die. It was enacted to prevent the wealthy from drawing down their estates prior to death to avoid or minimize the estate tax.

For 2024, you can transfer up to $18,000 to any individual without incurring the gift tax. It’s an annual figure that’s periodically increased for inflation.

How Much is the Gift Tax?

A common (and mistaken) assumption surrounds who pays the gift tax. Logically, you might expect that to be the recipient. After all, the amount of the gift constitutes income to that person, but that’s not how the gift tax works.

The gift tax is paid by the donor. That’s because, as an advance against the donor’s estate, it’s an attempt to minimize the estate tax.

However, if for any reason the donor does not pay the tax, it can become the responsibility of the recipient.

How much is the gift tax? It’s surprisingly high, even higher than the rate on income tax brackets.

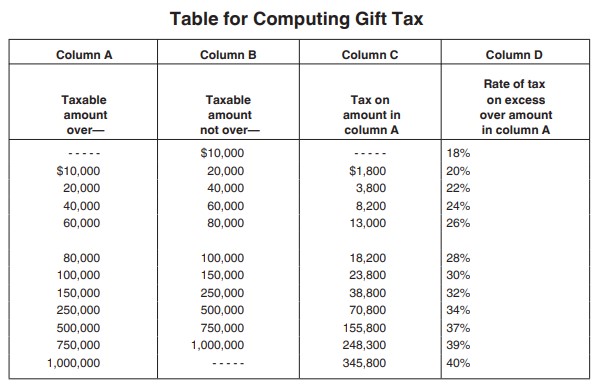

According to the 2023 Instructions for Form 709, United States Gift (and Generation-Skipping Transfer) Tax Return (Page 20), the tax rates on gifts that exceed the $18,000 annual gift exemption are as follows:

Based on this table, if you were to make the amount of the gift $50,000, you would pay no tax on the first $18,000, but 18% on the next $10,000 ($1,800), 20% on the next $10,000 ($2,000), plus 22% on the last $12,000 ($2,640).

The total tax on the $50,000 gift would come to $6,440. That helps to explain why those who want to give gifts are anxious to find ways to avoid having to pay the tax. Fortunately, there are several strategies for doing just that, which we’ll get into in a bit.

What is a Gift?

Anything is a gift but the things to be aware of are those that have substantial value and some kind of paper trail. If you give someone furniture, unless it’s an extremely valuable antique, no one will care. An IKEA dresser won’t even register. 😆

Cash is the most obvious type of gift. You can also any type of assets with an equivalent value, like stocks, bonds, certificates of deposit, investment funds, and other liquid assets.

Real property is also a gift. In fact, if you sell a piece of real estate to another party for less than its fair market value, it can represent a taxable gift. For example, let’s say you agree to sell your home – worth $300,000 – to your adult child for $200,000; $100,000 will be considered a gift.

A similar situation will apply to a forgiven debt. Let’s say you make a $50,000 loan to one of your adult children that’s later forgiven. Either the entire loan amount or the remaining outstanding principal balance will be considered a gift.

A gift can also be considered: an interest-free or below-market interest rate loan, transferring the benefits of insurance policy, the transfer of digital assets, and other asset classes. If you have any doubts, it’s always best to check with a tax professional.

However, there are certain transfers that are not subject to the gift tax, including:

- Contributions to political organizations and certain charitable organizations.

- Payments that qualify for the educational exclusion paid on behalf of the recipient.

- Payments that qualify for the medical exclusion, including health insurance premiums, paid on behalf of the recipient.

- Transfers of funds or assets to a spouse who is a US citizen.

- Funds given to a dependent.

Ways to Avoid Incurring the Gift Tax

There are several ways to avoid paying the gift tax. Gift transfers to your spouse are exempt if that spouse is a US citizen.

In addition, the $18,000 gift exemption can be doubled if each spouse gives a $18,000 gift to the same person totaling $36,000. That is, the $18,000 gift exclusion is the limit between one donor and one recipient, but two donors can double the gift to a single recipient.

It’s also worth noting that there’s no total limit on the number of $18,000 gift exemptions you can give to different recipients.

If you stay within the gift limits, you don’t have to file any paperwork.

But if you don’t…

How to File the IRS Form 709

If you want to exceed the $18,000 limit, you can do that by filing IRS Form 709, United States Gift (and Generation-Skipping Transfer) Tax Return. It needs to be filed for each year in which a gift exceeding $18,000 has been made. (accountants will charge, on average, $500 to file this form!)

What filing Form 709 does is provide an exclusion of the gift made. However, that exclusion – and any subsequent exclusions claimed – will represent a reduction of your lifetime estate exemption.

For example, let’s say you’re a single person, with a lifetime estate exclusion of $13,610,000. In 2024, you give $300,000 to one of your adult children. By filing Form 709, the $300,000 gift for the year is applied as a reduction to your lifetime exclusion. Therefore, no gift tax will be due on the 2024 transfer.

However, the $300,000 gift given in 2024 will reduce your lifetime estate exclusion. Based on the 2024 contribution, the lifetime exclusion will drop by $282,000. The same thing will happen for each year in which you give a gift to one or more recipients that exceeds the $18,000 annual, per person gift exemption.

In theory, you can gift the entire amount of your estate exclusion while you are still alive. Given that the amount of that lifetime exclusion increases just about every year – often substantially – you may never fully reach the exclusion amount.

Consider Professional Help

If you plan to give a gift to any single recipient that will be over $17,000, you’ll need to file Form 709. If so, you might want to consider a professional tax preparer. Form 709 is a much different tax return than an individual income tax return and requires special handling.

There’s another important reason for using a tax professional. Form 709 is something of a permanent tax record. Whatever is filed on the form will affect the cumulative value of your estate for the rest of your life and at the time of your death. Form 709 maintains a running total of how much of the exclusion you have taken and how much remains and you don’t want to mess it up.

Form 709 is definitely not a tax form for the certified do-it-yourselfer.

Penalties for making mistakes can be severe, so it’s best to turn the job over to someone who does it for a living.

Or stay under the gift tax limit. 🙂

Jim – I feel the real issue isn’t worrying about the current $11+ mil exemption. I agree it doesn’t impact very many folks. However, there’s no guarantee the exemption will remain at that level. If the progressive leaning politicians are voted in, it won’t be surprising to see them significantly reduce the exemption in the inheritance or dead tax. That’s why we’re worried. A lot of politicians are after your money. Be afraid!

While that’s true, I think to focus on something that may or may not come to fruition is a waste of time. There are plenty of other things to worry about, like whether the planet will be worth passing along to our children. 🙂